Welcome to THE MAKING OF A NATION - American history in VOA Special English.

As we said last week, James Buchanan of Pennsylvania won the presidential election of eighteen fifty-six. He defeated John Fremont, the candidate of the newly created Republican Party, which opposed slavery.

Buchanan, a Democrat, had often supported the South in the dispute over slavery. Most of the new president's closest friends were southerners. He wrote that the North was too aggressive toward the South and should stop interfering in the slave states.

Buchanan said the South had good reason to leave the Union if abolitionists continued their attacks against slavery.

This week on our series, Jack Moyles and Stan Busby tell more about James Buchanan. And they discuss his influence in the Supreme Court ruling in the case of a slave from Missouri named Dred Scott.

As the new president, Buchanan believed he could solve the slave question by keeping the abolitionists quiet. Success would mean the end of the anti-slavery Republican Party.

In choosing his cabinet, Buchanan wanted men who shared the same ideas and interests. President Pierce had tried to unite the different groups in the party by giving each a representative in his cabinet. This had not worked. It had driven the different party groups farther apart.

Buchanan had served in President Polk's cabinet. He remembered how well its members worked together. He said it was the unity of this cabinet that made Polk's administration so successful. Buchanan gave the job of Secretary of State to Lewis Cass of Michigan. Cass was seventy-five years old. His mind had lost its sharpness. This did not worry Buchanan, because he had planned to be his own foreign minister.

The job of treasury secretary went to Howell Cobb, a southern moderate from Georgia. Southerners also were named as secretary of war, interior secretary and postmaster general.

Isaac Toucey of Connecticut was given the job of Navy secretary. Toucey was a northerner. But he supported many policies of the South. Another northerner - Jeremiah Black of Pennsylvania - became attorney general.

In forming his cabinet, Buchanan did not ask for advice from Senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois. Douglas was the party's leader in the Senate and the most powerful Democrat in the northwest. Douglas believed that the northwest should have two representatives in the cabinet. He said Cass could be one of them. But Douglas wanted one of his own supporters to be the other. Buchanan refused what Douglas wanted. And he gave the administration's support to a political enemy of Douglas. James Buchanan was sworn-in as president on March fourth, eighteen fifty-seven. In his inaugural speech, the new president denounced the long dispute over slavery. He said he hoped it would end soon.

Buchanan said the dispute could be settled easily by doing two things: by ending interference with slavery in states where it was legal. And by letting the people of a territory decide if they wanted slavery.

Buchanan said he expected the Supreme Court to rule soon on the right of the people of a territory to decide this. He said he was sure that all good citizens - North and South - would accept the high court's ruling. At the time he said this, Buchanan already knew what the court's decision would be. He had even used his influence to help one member of the court to decide. The decision was made in the case of Dred Scott, a negro slave.

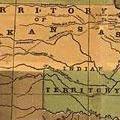

Scott was sold in Missouri to an army doctor who took him to Illinois and then went into the Wisconsin territory. Scott lived in these two places for almost four years before he was returned to Missouri.

Scott asked a court in Missouri to give him his freedom. He claimed that living in Illinois and Wisconsin - where slavery was illegal - had made him a free man.

The court agreed with Scott and gave him his freedom. But the decision was appealed, and the Supreme Court of Missouri ruled against him. Scott then took his case to a federal court. Finally, he asked the United States Supreme Court to decide if he was a slave or a free man.

The Supreme Court took up the case in December, eighteen fifty-six. The judges studied it carefully because it raised serious constitutional questions.

Scott claimed he was free because he had lived in free territory. It was free because Congress - in the Missouri Compromise of Eighteen Twenty - made slavery illegal in that area. Scott's owner raised the questions: Did Congress have the Constitutional power to close a territory to slavery? Was the Missouri Compromise legal?

At first, most of the nine Supreme Court judges had planned to give a decision without answering this question. They did not want to involve the court in this bitter dispute. The majority decided that a negro was not a citizen. Therefore, they said, Dred Scott had no right to ask the court to hear his case.

In this way, the case could be settled without deciding on the power of Congress to act on slavery in the territories. But two of the nine Supreme Court judges opposed this ruling. Both were from the North. They had said they would write a minority decision. They said their decision would include a statement that Congress did have power over slavery in the territories.

Since two members of the court had planned to offer views on this question, the other seven decided the majority also should do so.

Of the seven, five were from the South. They did not believe Congress had any power over territorial slavery. The remaining two judges - both from the North - did not want to make what they felt would be a political decision.

One southern member of the Supreme Court was James Catron, a good friend of James Buchanan. Buchanan had written to him asking when the court would act on the Dred Scott case.

Catron had answered that the court would rule soon. Then he asked for Buchanan's help in getting one of the northern members of the court to vote with the five from the South. He told the president that the country would more easily accept the court's ruling if one of the northern judges gave his support. Catron proposed that Buchanan write to Justice Robert Grier of Pennsylvania.

So Buchanan wrote to Grier. He told him that a strong decision in the Dred Scott case might do much to bring peace to the country. Grier agreed. He said he would vote with the five southerners. They would rule that the Constitution did not give Congress power over slavery in the territories.

All this had happened in the few weeks before Buchanan became president.

The Supreme Court finally announced its decision just two days after Buchanan moved into the White House. Chief Justice Roger Taney read the decision in the small courtroom in the Capitol building. The room was crowded with congressmen, senators, government officials, and newspapermen. Chief Justice Taney began reading the decision at eleven o'clock. He read for more than two and a half hours.

He said the high court rejected Scott's claim of freedom for three reasons. First, Scott was not a citizen. Taney said the Constitution gave the right of citizenship only to members of the white race. Because he was not a citizen, he had no right to ask the court to hear his case.

Secondly, Taney said Scott was ruled by the laws of Missouri, the state in which he lived. Missouri laws did not give freedom to slaves who lived temporarily in free territory. Therefore, said Taney, Scott was still a slave.

Then the chief justice took up the question of the free territory in which Scott had lived. It had become free territory under the Missouri Compromise. This was the law that Congress passed in eighteen twenty. This law kept slavery out of the northern part of the territory which the United States bought from France.

Justice Taney said Congress did not have the constitutional power to pass such a law. He said when new territory was won, it belonged to all citizens. He said Congress had the right to govern such territory until it became a state. But he said Congress did not have power to close new territory to any American citizen. He said the citizen from Georgia had as much right to settle in this territory with his slaves as a citizen of Maine with his horse.

Taney said there was no word in the Constitution that gave Congress greater power over slave property than over any other kind of property. The only such power Congress held was the power to guard and protect the rights of the property owner.

To close territory to slaves, Taney said, violated the constitutional rights of slaveholding citizens. Therefore, the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional. Congress did not have power to act on slavery in the territories.

Our program was written by Frank Beardsley. The narrators were Jack Moyles and Stan Busby. Transcripts, MP3s and podcasts of our programs can be found, along with historical images, at voaspecialenglish.com. And you can follow our series on Twitter at twitter.com/voalearnenglish, spelled as one word. Join us again next week for THE MAKING OF A NATION - an American history series in VOA Special English.

This is program #84 of THE MAKING OF A NATION Transcript of radio broadcast: 13 May 2009