Welcome to the MAKING OF A NATION - American history in VOA Special English.

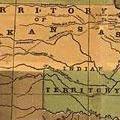

In eighteen fifty, the United States faced the threat of a split between northern and southern states. The two sides disagreed strongly over the issue of slavery. At that time, owning slaves was legal in the southern states. But the question remained: should slavery be legal in new territories in the western part of the country?

The issue needed to be settled. There was a danger of civil war between the North and the South. Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky offered a compromise. Conservative southern lawmakers rejected it. Other lawmakers supported it; they believed it was the only way to save the union of states.

This week in our series, Warren Scheer and Sarah Long continue our story of the Compromise of Eighteen Fifty.

One of the nation's top political leaders, Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, supported Henry Clay's compromise. Webster believed that slavery was evil. Yet he believed that national unity was more important. He did not want the nation to divide. He did not want to see the end of the United States of America.

Daniel Webster spoke to other members of the Senate. His speech was an appeal to both sides in the dispute.

"I speak today," he said, "to save the Union. I speak today out of a concerned and troubled heart. I speak for the return of a spirit of unity. I speak for the return of that general feeling of agreement which makes the blessings of this union so special to us all." Senator Webster spoke of how he hated slavery. He spoke of his fight against the spread of slavery in America. But he disagreed with those who wanted laws making slavery illegal in new territories. It would not be wise to pass such laws, he said. They would only make the South angry. They would only push the South away from the Union.

Then Webster spoke about the things the North and South had done to make each other angry.

One, he said, was the failure of the North to return runaway slaves. He said the South had good reason to protest. It was a matter of law. The law was contained in article four of the national constitution.

"Every member of every northern legislature," Webster said, "has sworn to support the constitution of the United States. And the constitution says that states must return runaway slaves to their owners. This part of the constitution has as much power as any other part. It must be obeyed." Next, Webster spoke about the Abolition societies. These were organizations that demanded an end to slavery everywhere in the country.

"I do not think that Abolition societies are useful," Webster said. "At the same time, I believe that thousands of their members are honest and good citizens who feel they must do something for liberty. However, their interference with the South has produced trouble." As an example, Webster spoke about the state of Virginia. Slavery was legal there. Webster noted that public opinion in Virginia had been turning against slavery until Abolitionists angered the people. After that, he said, no one would talk openly against slavery. He said Abolitionists were not ending slavery, but helping it to continue.

Then Webster said the North also had a right to protest about some things the South had done.

He said the South was wrong to try to take slaves into new American territories. He said attempts to do this violated earlier agreements to limit slavery to areas where it already existed.

Webster said the North also had a right to protest statements by southern leaders about working conditions in the North. Southerners often said that slaves in the South lived better lives than free workers in the North.

Webster appealed to both sides to forgive each other. He urged them to come to an agreement. He said the South could never leave the Union without violence.

Webster said the two sides were joined together socially, economically, culturally, and in many other ways. There was no way to divide them. No Congress, he said, could establish a border between the North and South that either side would accept.

In general, Webster's speech to the Senate was moderate. He wanted to appeal to reason, not emotion. Yet it was difficult for him to be unemotional. His voice rose as he finished.

"Secession!" He called out. "Peaceable secession! Your eyes and mine will never see that happen. There can be no such thing as peaceable secession. We live under a great constitution. Is it to be melted away by secession, as the snows of a mountain are melted away under the sun?" "Let us not speak of the possibility of secession. Let us not debate an idea so full of horror. Let us not live with the thought of such darkness. Instead, let us come out into the light of day. Let us enjoy the fresh air of liberty and union." Northern Abolitionists quickly criticized Daniel Webster's speech. They called him a traitor. Yet most people of the North accepted Webster's appeal for compromise. His speech cooled the debate that threatened a complete break between the North and South.

The dispute about slavery continued in the United States. It would, in time, lead to civil war. But historians say Webster's support for the compromise of eighteen fifty probably helped delay that crisis. Daniel Webster's speech was not the end of debate on the compromise. Four days later, Senator William Seward of New York rose to speak.

Seward said he opposed any compromise with the South. He said he did not want slavery in the new western territories. And he urged a national policy to start ending slavery everywhere - peacefully.

Seward criticized Daniel Webster for speaking against the Abolition societies. He said such groups represented a moral movement that could not be stopped. He said the movement would continue until all the slaves in America were free.

Seward then criticized another senator, John C. Calhoun of South Carolina. He denounced Calhoun's demands for a political balance between the North and South. He said this would change the United States from a united, national democracy to an alliance of independent states. In such a system, he said, the minority would be able to veto actions of the majority.

Many lawmakers seemed to support the idea of Clay's compromise. But they could not agree on which parts of it to pass first. Southern supporters were afraid that if a statehood bill for California was passed first, then northerners would refuse to pass the other parts of the compromise. So, southerners wanted to include all parts in one bill.

Hopes for the compromise increased after the death of John C. Calhoun on the last day of March, eighteen-fifty. Calhoun was pro-slavery. He had refused to compromise on the issue. One newspaper in Calhoun's state of South Carolina said: "The senator's death is best for the country and his own honor. The slavery question will now be settled. Calhoun would have blocked a settlement." A committee of thirteen men was named to write a bill based on Henry Clay's compromise. The committee had six members from slave states and six from free states. Henry Clay was named to lead it.

Three weeks later, the committee offered its bill. It was much like the compromise Clay had first proposed. It made California a free state. It created territorial governments for New Mexico and Utah. It settled the border dispute between Texas and New Mexico. It ended the slave trade in the District of Columbia. And it urged approval of a new law dealing with runaway slaves.

For about a month, the proposed bill seemed to have the support of the administration of President Zachary Taylor. But then, President Taylor made it clear that he would do everything he could to defeat it.

That will be our story next week. Our program was written by Frank Beardsley. The narrators were Warren Scheer and Sarah Long.

Transcripts, MP3s and podcasts of our programs are online, along with historical images, at voaspecialenglish.com. Join us again next week for THE MAKING OF A NATION -- an American history series in VOA Special English.

This is program #78 of THE MAKING OF A NATION Transcript of radio broadcast: 01 April 2009