Welcome to the MAKING OF A NATION – American history in VOA Special English.

In the summer of eighteen fifty-eight, two candidates campaigned across the state of Illinois for a seat in the United States Senate. That seat belonged to Stephen Douglas from the Democratic Party. He was seeking re-election. His opponent was a lawyer from the newly established Republican Party. His name was Abraham Lincoln.

This week in our series, Frank Oliver and Larry West tell us about this campaign of statewide but also national importance.

Abraham Lincoln proposed that he and Stephen Douglas hold several debates. The rules for each debate would be the same. One man would speak for an hour. His opponent would speak for an hour and a half. Then the first man would speak for half an hour to close the debate. Douglas agreed.

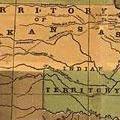

There were seven debates in all. They were held in towns throughout Illinois. In some places, there was great interest in what the two candidates had to say. Thousands of people attended.

Douglas was a short, heavy man. One reporter said he looked like a fierce bulldog. Douglas's friends and supporters called him "the little giant." Lincoln was just the opposite. He was very tall and thin, with long arms and legs. His clothes did not fit well. And he had a plain face, one which many thought was ugly. He looked more like a simple farmer than a candidate for the United States Senate.

The Lincoln-Douglas debates covered party politics and the future of the nation. But everything the two men discussed was tied to one issue: slavery.

Douglas spoke first at the first debate. He questioned a statement made in one of Lincoln's campaign speeches. Lincoln had said that the United States could not continue to permit slavery in some areas, while banning it in others. He said the Union could not stand so divided. It must either permit slavery everywhere - or nowhere.

Douglas did not agree. He noted that the country had been half-slave and half-free for seventy years. Why then, he asked, should it not continue to exist that way. The United States was a big country. What was best for one part might not be best for another.

Then Douglas questioned Lincoln's statement on the Supreme Court's Dred Scott decision. Lincoln had said he opposed the decision, because it did not permit Negroes to enjoy the rights of citizenship.

Douglas said he believed the decision was correct. He said it was clear that the government had been made by white men, for white men. He said he opposed Negro citizenship.

"I do not accept the Negro as my equal," Douglas said. "And I deny that he is my brother. However," he said, "this does not mean I believe that Negroes should be slaves. Negroes should enjoy every possible right that does not threaten the safety of the society in which they live." "Every state and territory must decide for itself what these rights will be. Illinois decided that Negroes will not be citizens, but that it will protect their life, property, and civil rights. It keeps from Negroes only political rights, and refuses to make Negroes equal to white men. That policy satisfies me," Douglas said. "And, it satisfies the Democratic Party." Then Lincoln spoke.

First, he denied that the Republican Party was an Abolitionist party." I have no purpose," he said, "either directly or indirectly, to interfere with slavery where it exists. I believe I have no legal right to do so. Nor do I wish to do so. I do not," Lincoln said, "wish to propose political and social equality between the white and black races." "But," he went on, "there is no reason in the world why Negroes should not have all the natural rights listed in the Declaration of Independence. The right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

"I agree with Judge Douglas," Lincoln said, "that the Negro is not my equal in many ways - certainly not in color, perhaps not mentally or morally. But in the right to eat the bread that his own hand earns, he is my equal and the equal of Judge Douglas, and the equal of every living man." Lincoln then defended his statement that the United States could not continue half slave and half free.

He said he did not mean that customs or institutions must be the same in every state. He said it was healthy and necessary for differences to exist in a country so large. He said different customs and institutions helped unite the country, not divide it.

But Lincoln questioned if slavery was such an institution. He said slavery had not tied the states of the Union together, but had always been an issue that divided them.

How had the country existed half-slave and half-free for so many years, Lincoln asked. Because, he said, the men who created the government believed that slavery was only temporary. Once people understood that slavery was not permanent, the crisis would pass.

Slavery could be left alone in the South until it slowly died. That way, Lincoln said, would be best for both the white and black races.

Stephen Douglas and Abraham Lincoln were campaigning for a Senate seat from the state of Illinois. But their debates had national importance, too.

Douglas expected to be the Democratic candidate for president in eighteen sixty. His statements could win or lose him support for that contest. Whenever possible, he tried to show that he was a man of the people, like Lincoln. He tried to show that his Democratic Party was a national party, while the Republican Party was a party only of the North. And he tried to show that Lincoln's policies would lead to civil war. Lincoln, for his part, may have looked like a simple farmer. But he was a very smart lawyer and politician. He asked questions which he knew would cause trouble for Douglas. He wanted to create a split between Douglas and his supporters in the South.

Lincoln also wanted to keep alive the debate over slavery. "That," he said, "is the real issue. That is the issue that will continue in this country when these poor tongues of Judge Douglas and myself are silent. It is the eternal struggle between right and wrong." In Illinois in eighteen fifty-eight, the state legislature chose the men who would represent the state in the national Senate. So Stephen Douglas and Abraham Lincoln had to depend on legislative support to get to Washington.

On Election Day, the legislative candidates supporting Lincoln won four thousand more popular votes than the candidates supporting Douglas. But because of the way election areas had been organized, the Douglas Democrats won a majority of seats. The newly elected legislature chose him to be senator.

Lincoln was sad that he had not won. But he said he was glad to have tried. The campaign, he said, "gave me a hearing on the great question of the age, which I could have had in no other way. And though I now sink out of view and shall be forgotten, I believe I have made some marks which will tell for the cause of civil liberty long after I have gone." Many people, however, did not think Abraham Lincoln would be forgotten. His campaign speeches had been published everywhere in the East. His name was becoming widely known. People began to speak of him as a presidential candidate.

To win the presidential election of eighteen sixty, the Republican Party had decided it needed a man of the people. He must be a good politician and leader. He must be opposed to slavery, but not too extreme. Many people thought Lincoln could be that man.

After the election in Illinois, Lincoln made several speaking trips in the western states. In none of his speeches did he say he might be a candidate for president in eighteen sixty.

If anyone said anything about "Lincoln for president," he would answer that he did not have the ability. Or he would say there were better men in the party than himself. Lincoln said: "Only events can make a president." He would wait for those events.

Our program was written by Frank Beardsley. The narrators were Frank Oliver and Larry West.

Transcripts, MP3s and podcasts of our programs are online, along with historical images, at voaspecialenglish.com. Join us again next week for THE MAKING OF A NATION - an American history series in VOA Special English.

This is program #88 of THE MAKING OF A NATION Transcript of radio broadcast: 11 June 2009