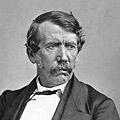

David Livingstone Part 2

After putting the family on a ship back to Scotland, David was in Kuruman when he got news that the Boers had attacked Chief Sechele and the mission station at Kolobeng. Along with the Boers enslaving hundreds of the Bakwain, they killed 60 of Sechele's tribesmen. The chief escaped with some of his tribe. The Boers destroyed everything that David owned. All he had left was what was with him on his trip to the coast. He had lost all of his books, medical equipment and medicines in the raid. At that time David decided to no longer have a mission station where he would call home. He would be a permanent explorer.

His next great trek led him to the west coast of Africa to Loanda (now known as the capital of Angola–Luanda). Without the help of a Portuguese Sergeant, he and his expedition team would probably have been murdered in the trek. The Portuguese military provided David and his crew with any food and clothing they felt necessary after their narrow escape from the Bashinji tribe.

On May 31, 1854 (when David was 41 years old) he had completed the 2000 mile trip from the mission station at Kuruman southern Africa, through the Kalahari desert and the west African jungle to the west coast.

From the coast David was offered a ride home on the British ship the Forerunner. He refused the offer because he had promised a chief that he would bring his men back to him safe and sound once the expedition was over. However, Livingstone did send letters and reports back on the Forerunner. Unfortunately, the ship had been wrecked and all hands were lost along with his documents. He was greatly troubled by the loss of life. He then had to recreate his documents as much as possible, which took several weeks.

When David returned the native helpers back to their chief, the chief was shocked. They had been gone almost 2 years. There was a general sense that all were lost. The arrival of all the men started a week's worth of celebration and storytelling. He immediately turned his thoughts to exploring the Zambezi river once again. His purpose was to find easy access from the coast to the interior of Africa. The trip to Loanda proved that going through the west was not a feasible route.

Four years after discovering the Zambezi, he finally stood at the top of “the smoke that thunders.” The noise surrounding him was so loud that using signs was the only way that he and his men could communicate. He stood on an island in the middle of the river and carved his initials and the year 1855 in a tree at the top of Victoria Falls.

In May of 1856 he made it to the east coast of Africa by following the Zambezi. He wrote a letter to the London Missionary Society telling them that he had found a way to get missionaries into the interior and that there would be many places that he mapped out that would be prime locations for mission stations.

David secured passage back to Scotland to be with his family. His promise to join them in 2 years took 4-1/2 to be realized. On his trip home he got news that his father had died. While he was excited to be with his family again, he often chided himself with the thought that maybe he should have returned home sooner. He left home as a 27 year old, green missionary doctor. He returned for the first time as a 43 year old seasoned explorer.

His wife had not adjusted well to living in civilization. She only stayed with David's family a short time and then went to England to be with some of her parents' friends. While home, David was asked to give many speeches on his journeys through Africa. He was honored by the Royal Geographical Society with a gold medal. They asked him to give a speech and he was encouraged to render the following words after looking into the crowd and seeing his old friend Cotton Oswell.

I am only doing my duty as a missionary in opening up a part of Africa to the sympathy of Christ. I am only just now buckling my armor for the good fight. I have no right to boast of anything. I will not boast until the last slave in Africa is free and Africa is open to honest trade and the light of Christianity.

He also spent a great deal of time speaking on behalf of the London Missionary Society. He urged more people to take up the call to missions. The LMS also encouraged David to return to Africa and open a permanent mission station of his own. It still did not see the value in the work Dr. Livingstone was doing as an explorer.

He was then offered a government position with a salary of 5 times more than his missionary salary. His government postion was as an explorer. He was also given a book publishing offer. With these two offers he was able to part ways with the LMS. Not because of doctrinal issues or because he ceased to have a desire for missions, but because, without the guiding hand of the LMS, he was finally able to perform the task that he felt God-called to do.

During this time his “big chief” (Queen Victoria) requested a private audience with him. She burst into laughter when David told her that the chiefs in Africa were always amazed that Livingstone had never met his own “big chief.” In 1858, David, Mary and their youngest son Zouga returned to Africa. After their return to Africa he attempted to make the trip up the Zambezi river all the way to Victoria falls in a steam powered paddle boat. On his trip down the river two years previous, he by-passed a segment of the river to make the trip shorter. Little did he know at that time that there were rapids that would be un-navigable. His efforts to return to the falls by a large boat was thwarted.

The team with which he set out had little to no understanding of the great trials David had endured in Africa. Though they all read his book, he was very uncomplaining within its covers. The reality of life in Africa was much more difficult. Ultimately, David seemed to blame himself for the loss of missionary's lives because they came to Africa without a full appreciation of how hard and disease filled the life in Africa actually was. As he continued to explore from the eastern edge of the continent he began to see more and more evidence of the slave trade. David began to focus on the abolishment of such a crime against humanity.

Just four years after their return to Africa, Mary Livingstone became ill with malaria. It was her first infection and she died within a week at the age of 41. He wrote in his journal: It is the first heavy stroke I have suffered, and quite takes away my strength. I wept over her who well deserved many tears. I loved her when I married her, and the longer I lived with her I loved her the more. God pity the poor children, who were all tenderly attached to her, and I am left alone in the world by one whom I felt to be a part of myself. I hope it may, by divine grace, lead me to realize heaven as my home, and that she has but preceded me in the journey. Oh my Mary, my Mary! how often we have longed for a quiet home, since you and I were cast adrift at Kolobeng…For the first time in my life I feel willing to die.

Livingstone still had 11 years to work in the dark but brightening continent of Africa.

A couple years after the passing of his wife, he took a trip back home to see his children. But before making the trip home, he made a trip to India. The trip to India was to sell his flat bottomed river boat. He could not afford to have his valuable boat fall into the hands of slave traders. So he sailed from Zanzibar, Africa to Bombay, India arriving in June of 1864. For some reason, he had a bit of trouble convincing the port authority in Bombay that he really did cross the ocean in a riverboat.

On his second trip home he wrote another book in which he detailed the mapping of the Zambezi River and he gave lectures talking of the needs for legitimate trade with Africa to help end slavery.

In August of 1865 he left England for the last time. His mother died while he was home and he received news that his oldest son Robert had died in a prisoner of war camp while fighting in the American Civil War.

On his next expedition he came down with a relapse of his malaria. During this trip his medicine box was stolen. He knew that it would probably be just a matter of time before he would succumb to the disease. The thieves of his medicine box returned to the coast and reported that Livingstone had died. They brought the medicine box as proof of this.

A search party was organized to find the venerable explorer. They never caught up with him, but there was plenty of evidence to say that the great Dr. David Livingstone was still alive.

He fell into a party of Arabic slave traders. Though he despised their work, he traveled with them in an attempt to share the Gospel with them in hopes of stopping the trade from the inside. Livingstone was, and is still today, criticized for receiving help from the slave traders. Without their help, he would have died sooner from his malaria.

He traveled off and on with the slave traders, mostly traveling by himself and as few as 6 African helpers for the next several years.

November 3, 1871 had the great missionary, David Livingstone, meeting with Henry Morton Stanley. Stanley walked into the village of Ujiji carrying an American flag and uttering the words “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” Stanley brought letters from home and news from the outside world. They explored the region together for a short time in which Livingstone learned that the lake he was studying, and hoping would be the source of the Nile, turned out to not be what he had hoped. They spent three months together in which Stanley attempted to convince Livingstone to return to the coast. Stanley returned with letters and journals from Dr. Livingstone. That was the last time any white person would see Livingstone alive.

During the night of April 30, 1873 Livingstone climbed out of his cot and kneeled down and crossed his hands in prayer. He was still in that position when his body was found the next day.

His three African helpers, Susi, Chuma and Jacob Wainwright prepared David's body for the trip back to the coast and, ultimately, to Great Britain. They removed his heart and buried it under a mvula (or mpundu) tree. Then they carried his body over 1,000 miles to the coast, through war zones, swamps and jungles. It took them 8 months to arrive. Jacob Wainwright, since he spoke English better than the other two, was asked to accompany David's body back to England. Once in London an autopsy was performed on the body for proof that it was, indeed, Dr. David Livingstone. They needed only check the bones of his upper left arm and knew that they were in possession of the Doctor's body. The lion attack of 30 years previous was used to identify him.

Eleven and a half months after he died, David Livingstone's body was laid to rest at Westminster Abbey. His gravestone reads: BROUGHT BY FAITHFUL HANDS OVER LAND AND SEA HERE RESTS DAVID LIVINGSTONE, MISSIONARY, TRAVELLER, PHILANTHROPIST, BORN MARCH 19. 1813 AT BLANTYRE, LANARKSHIRE, DIED MAY 1, 1873 AT CHITAMBO'S VILLAGE, ULALA. FOR 30 YEARS HIS LIFE WAS SPENT IN AN UNWEARIED EFFORT TO EVANGELIZE THE NATIVE RACES, TO EXPLORE THE UNDISCOVERED SECRETS, TO ABOLISH THE DESOLATING SLAVE TRADE, OF CENTRAL AFRICA, WHERE WITH HIS LAST WORDS HE WROTE, “ALL I CAN ADD IN MY SOLITUDE, IS, MAY HEAVEN'S RICH BLESSING COME DOWN ON EVERY ONE, AMERICAN, ENGLISH, OR TURK, WHO WILL HELP TO HEAL THIS OPEN SORE OF THE WORLD” Speaking at a 100 year celebration of the birth of Dr. Livingstone, Lord Cruzon, president of the Royal Geographical Society said: In the course of his wonderful career, Livingstone served three masters. As a missionary he was the sincere and zealous servant of God. As an explorer he was the indefatigable servant of science. As a denouncer of the slave trade he was the fiery servant of humanity.